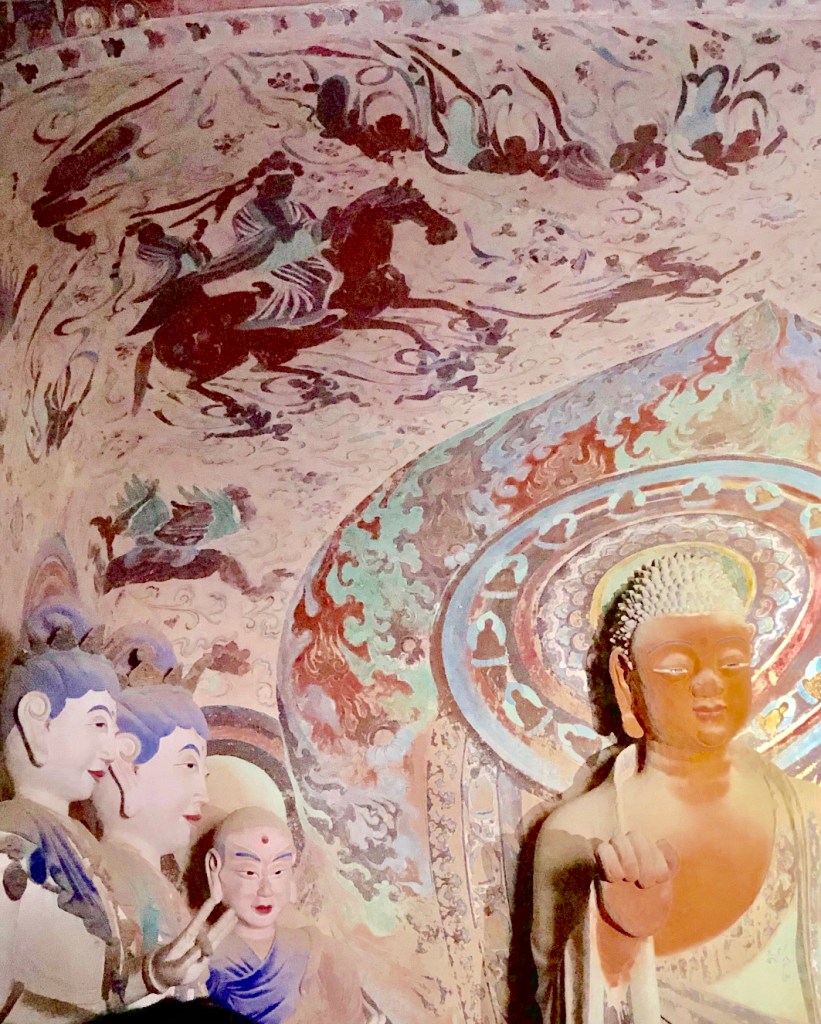

(Photo by Amitav Acharya)

In Sanskrit, the term Nirvana literally means transcendence. A Buddhist concept, it is also closely related to the Hindu idea of Moksa, meaning liberation or salvation. But just as the Silk Road is not about silk – many other goods were traded through it and China was not always the provider of these goods – the Nirvana Route, the concept I discuss here, is not just about Nirvana.

The Nirvana Routes captures the story of the spread of Buddhism from India to China (and then to Korea and Japan), and that of Hinduism and Buddhism to Southeast Asia. It also harks back to the encounters in literature, arts, trade and politics, for a millennium and a half, from the first century to the 16th century AD and beyond – encounters that laid the cultural foundations of modern Asia.

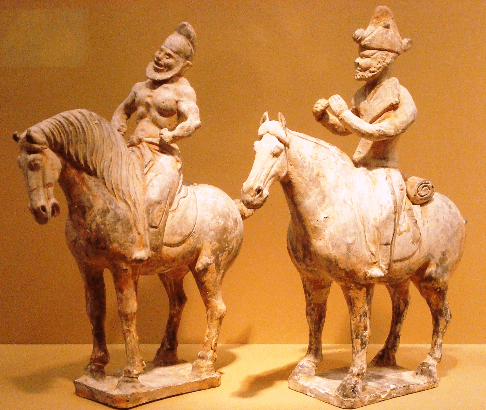

(Painted pottery foreign horse riders dated around 701AD, Xian History Museum. Photo by Amitav Acharya)

While the term Silk Road (or Silk Roads), has gained much prominence in academic and policy worlds, it is a 19th century term which obscures the fact that silk was not the most traded commodity or idea in Asia. That was Buddhism and the religious, cultural and political ideas and modes of living that came with it. The Silk Roads were founded by Buddhist traffic, especially the two-way travels – by land and sea – of monks, scriptures and translators, one of the most famous being the 7th century Chinese monk Xuanzang who spent 16 years in India studying Buddhism, acquiring Buddhist text and even mediating on Buddhist theological differences. Through the arrival of Indian monks in China and vice versa, the flow of Buddhist ideas and imagery among India, China, Korea, Japan, and central and Southeast Asian societies, and the role of Buddhist ideas in shaping political authority in these countries, there emerged a pan-Asian belief system and a shared way of life without which the modern idea of Asia would not have been conceivable.

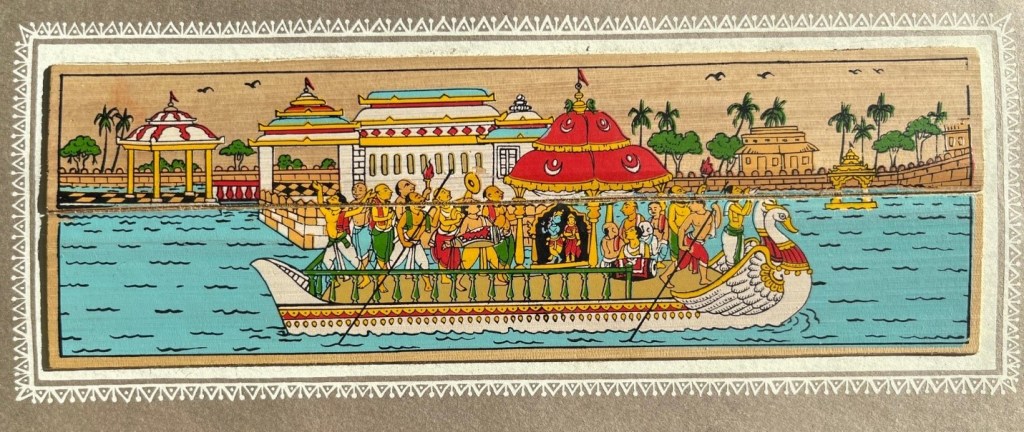

(A contemporary illustration of an ancient maritime voyage from the coast of Odisha, India. Photo by Amitav Acharya)

The Nirvana Routes also provided the foundation for the arrival of Islam from Western Asia to Southeast Asia via the Indian Ocean and the extensive and efficient Mongol transport and communication system that developed between China and Europe through the Central Asian region, which carried goods (much more than silk) as well as ideas of science, technology, and medicine. Later on, European powers took advantage of these pre-established connectivity to establish and expand their dominance over much of Asia. Today, as a divided and fragmented Asia searches for new ways of achieving cooperation and revitalizing itself, recapturing the Nirvana Routes might provide a template for the building its peace, prosperity, and progress.